ARCHITECTURE INTO ART: A DIALOGUE CLOSES THE CENTRO BOTÍN’S 2020 EXHIBITIONS PROGRAMME

- This exhibition engages in a dialogue with the built fabric of the Fundación Botín art centre in Santander, while addressing the relationship that artists have with the space in which they present their works.

- Curated by Benjamin Weil, artistic director of the Centro Botín, the exhibition will be open to the public from 9 October 2020 to 14 March 2021.

- Leonor Antunes, Miroslaw Balka, Carlos Bunga, Martin Creed, Patricia Dauder, Fernanda Fragateiro, Carlos Garaicoa, Carsten Höller, Julie Mehretu, Jorge Méndez-Blake, Muntadas, Juan Navarro Baldeweg, Sara Ramo, Anri Sala and Julião Sarmento will all be represented in the show.

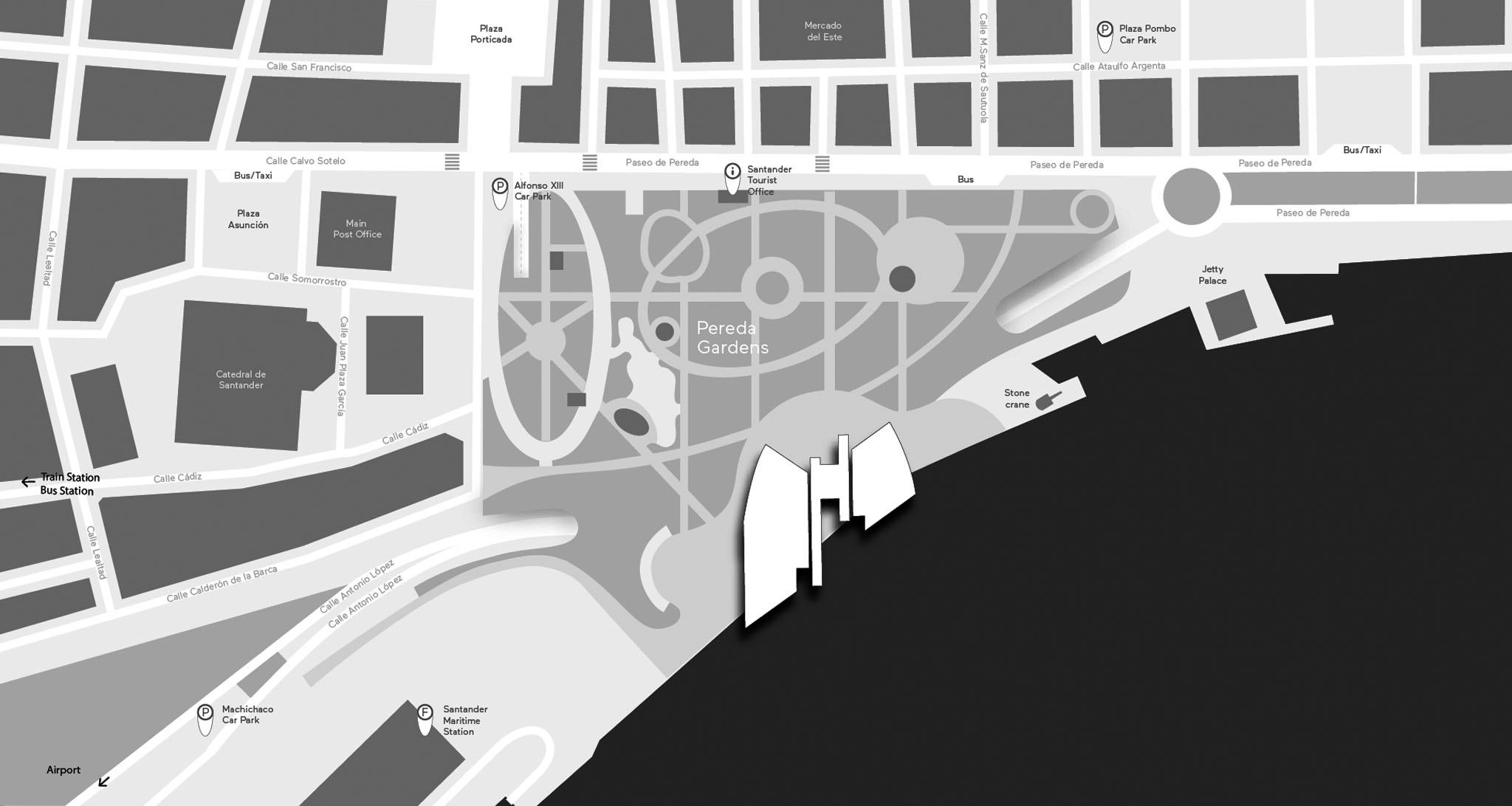

Centro Botín presents Architecture into Art: A Dialogue, a major new exhibition, open to the public from 9 October 2020 to 14 March 2021. The show conducts a conversation with Renzo Piano’s building, which has become an icon and a landmark of Santander’s Paseo Marítimo since it opened in June 2017, and addresses the relationship that artists establish with the physical site in which they show their work, the strategies by which they appropriate the exhibition space and the architectural space, investigating the mutual influence architecture and art exert on one another and offering reflections on how architecture shapes our lives and articulates social interaction and how while art brings viewers closer to reality from new angles.

Architecture into Art: A Dialogue, which will be open to the public from 9 October 2020 to 14 March 2021, brings together a selection of works by artists who have run one of the Fundación Botín’s Visual Arts Workshops and exhibited their work in Santander, along with pieces created by former recipients of the Foundation’s annual Visual Arts Grants. Thus, we can see works by Leonor Antunes, Miroslaw Balka, Carlos Bunga, Martin Creed, Patricia Dauder, Fernanda Fragateiro, Carlos Garaicoa, Carsten Höller, Julie Mehretu, Jorge Méndez-Blake, Muntadas, Juan Navarro Baldeweg, Sara Ramo, Anri Sala and Julião Sarmento – for all of whom architecture is a crucial concern to the point of affecting, in some cases, the formal definition of their artistic research.

In the words of Benjamin Weil, artistic director of the Centro Botín and curator of the exhibition: ‘If the original purpose of built structures was to provide a roof for human groups and their domesticated animals, nowadays they also serve as an agora in which a whole spectrum of social functions are carried out, ranging from commercial and administrative activities to professional practices and cultural spaces, such as museums.’

It has become increasingly common for new museums to be designed by internationally acclaimed architects. The Centro Botín is one of the most recent art spaces of the many devised by Renzo Piano, whose roster of built work includes the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Fondation Beyeler in Basel and (in collaboration with Richard Rogers) the iconic Centre Pompidou in Paris.

The functionality of the architecture

If the object of architecture is, in the first instance, functional, the fact that its dominant criterion is utilitarian does not preclude aesthetic concerns. Thus, the early 20th century witnessed the emergence of the highly influential Modern Movement, with its core principle that “form follows function”, a tenet perfectly exemplified by the work of Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus architects – Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer or Mies van der Rohe, among others.

A rigorously functional approach to the design of buildings and furniture was central to the thinking of a number of artists whose pursuit of a new purity of form, some sixty years ago now, led to the parsimonious use of carefully selected materials to produce objects bearing simplified geometric forms. These artists were also committed to engaging with the exhibition space as an integral part of their artistic reflection and art practice, including the perceptual twists resulting from the dynamic relationship between a sculptural object, colour or light and the space in question.

Architects think up buildings, and only occasionally involve themselves in their construction, delegating that task to engineers or other qualified professionals and limiting their input to supervising the process to ensure that the building is true to its original design and intention. Many minimalist artists followed the architects’ example in this, dissociating themselves from the process of material elaboration whose basis is the initial idea. Effectively shunning the craft aspect of work and aspiring instead to achieve formal purity and entrusting others with the actual embodiment of their works, their goal was to achieve the neutrality and perfection of the industrially produced object. The originality of the work did not depend on the fact that the artist had produced it with his or her own hands. Rather, the concept materialised in the work was privileged over manual dexterity.

EXHIBITION ITINERARY

The exhibition occupies the second floor galleries at Centro Botín, shared between two spaces separated by an open, diaphanous wall, which sets the rhythm of the exhibition. While the first room is dedicated to works in two dimensions, the works in the second room are three-dimensional, reflecting the idea of architecture as both object and subject, though it is not easy to define the actual borderline in many of the pieces in the show.

Architecture as object

Many of the works in this exhibition are formally indebted to the philosophy of Minimalism. In many cases the artists only worked on the concept, leaving to others the task of physically creating the works. This is the case of Seven Sliding Doors Corridor (2016), by Carsten Höller, which uses electronic mechanisms and materials to generate a prototypical physical experience of modernity, combining references to corporate architecture and science fiction. The piece consists of a corridor with seven sliding doors and a reflective surface which has different degrees of opacity or transparency, through which it is possible to see from inside to outside or from outside to inside. For Benjamin Weil, this work ‘establishes the sculpture as a space within the architectural space and reflects on how these two spaces relate to one another through the dynamic established between what this sculpture occupies and the sculpture itself.’

The same room also houses Anri Sala’s No Window No Cry (Renzo Piano & Richard Rodgers, Centre Pompidou, Paris) (2012), consisting of a full-scale replica of a window of the famous Paris museum, where this piece was first shown. Placed here in front of the Centro Botín window, the work establishes a relationship between windows in the first museum designed by Renzo Piano (Pompidou Centre) and in one of the most recent (Centro Botín), bringing out a certain degree of formal continuity between the two buildings despite the forty years that separate them. In its new location, the window enables Sala to frame the view and in so doing appropriate it, in clear reference to the art-historical concept of the veduta.

Since the early nineties, Miroslaw Balka has been listening to the architecture of the settings in which he exhibits his sculptures. Always in dialogue with space, he considers that the footprint that remains in architecture is architecture. His piece here, 196 x 230 x 141 (2007), consists of a hollow triangular structure which suggests the entrance to another space – to a mine, perhaps – with the bare bulb that illuminates its interior turning off as soon as the visitor approaches and enters a corridor, which gets narrower. The sculptural presence of this object, too, clearly alludes to architecture.

The work by Jorge Méndez-Blake, From the Bottom of a Shipwreck (2011), uses bricks to construct two tower-like structures, which allude to the architecture of the first industrial era in a theatrical mise en scène of a volume of Stéphane Mallarmé’s Symbolist poetry and function, in some sense, as a pair of hugely oversized bookends or suggest the walls of a library.

For Benjamin Weil, artistic director of the Centro Botín and curator of the exhibition, ‘there are artists who choose to create work that take direct inspiration from the linguistic structure of architecture; others, in contrast, opt to address themes that have more to do with the ornamental aspect, in order to posit, perhaps, a reflection on the status of the work of art in the building’. The fact is that although architects are often personally involved in the finishing of their constructions, in some instances the finish is the result of collaboration with a visual or decorative artists. For this reason, a number of the works in Architecture into Art: A Dialogue invoke the great tradition of fresco painting and monumental sculpture, which occupies a central place in the history of architecture. For example, in Attempt at Conservation (2014)Carlos Bunga chooses to enclose a three-dimensional painting on cardboard in a display case set into the wall of the room, while Sara Ramo makes a direct reference to architecture with two works that formally allude to the decorative arts: Intractable (tribute to Ivens Machado) (2019), a column of monumental proportions; and Slit (2019), an incision in the wall, in which the artist places various objects she has collected. For Ramo, every built space is a shell, a skin or a mask, and as an artist she seeks to turn buildings around, dig up the floors, get behind the plaster, dress the columns, open little doors… As she herself remarks, ‘You have to look for the entrails of the space and invoke the instinctive, inaugural architecture, the cave-architecture and the ceiling-architecture, shelter a spirit, make room for a void. Dig down and see the population of a strange common imaginary embody itself, become flesh and matter and insist precisely on a void full of life. An empty continent housed by walls, ceilings and pipes.’

Martin Creed‘s mural piece, Work No. 2696 (2016), generates a distortion of our spatial perception with a composition of coloured pigments and mirror stripes, materials traditionally used in the decorative arts. Though its occupation of the space is decidedly minimalist on a visual level, the work makes a big impression thanks to the dual presence of the painting itself and the mirrored stripes that reflect the space.

Anri Sala’s All of a Tremble (Encounter I) (2017) takes the shape of a projection screen covered in wallpaper that obstructs the view of the city. Saka takes his cue from the process of semi-industrial wallpaper production to create a musical instrument – actually made from rollers once used to produce the painted patterns. The hand-drawn motifs on the wallpaper appear at first to be the work of the mechanism we see affixed to the wall. It seems impossible to determine whether the roller is printing on the wall, or is interpreting the wallpaper patterns as if they were musical scores. Getting closer, one comes to realize the two halves of the wallpaper printing rollers activate a set of metal tines that turn the motifs on the paper into a melody. However, it remains unclear if the sound configures the image or if it is the image that produces the sound.

The structure of Leonor Antunes’s diaphanous hanging mesh metal scrim is inspired by patterns found in traditional weavings from Oaxaca (Mexico); while the piece is essentially related to decorative arts, it also has a very powerful architectonic presence.

The piece by Patricia Dauder, Floor (2018), consists ofa set of ninety worn pieces of parquet flooring, laid down in the exhibition space to form a rectangle on which the artist has placed an apparently burnt work on paper. Floor relates directly to the architecture of the space it occupies and reflects on the memory trapped in architectural elements, while its structure also gestures towards Minimalist art. The parquet has been torn up and removed from the place where it had a function, and it is this displacement that transforms it into sculpture. The work originated in 2011, when the artist used to walk around Brooklyn and Queens discovering a dark old city that did not conceal its decadence and exposed to view the layers of history its houses contained. Floor is just a delimitation on the ground, almost without volume, without body; a listless layer of eroded materials. But, at the same time, it is the vestige of a hypothetical dwelling and the memory of those who occupied it. According to Dauder, ‘the ground beneath our feet is also the place into which all that has vanished goes and where we find the remains of old buildings, of old shelters. Under the ground lies the subterranean, hidden from view; past stories, the negative of architecture’.

Architecture as subject

The work of Modernist architects have inspired a series of works by Juliao Sarmento, who trained as an architect before turning to art. ‘In his painting, architecture has a very strong presence, and not only on a literal level but also in relation to the construction of his pictorial space,’ says Benjamin Weil. For instance, the title of the canvas Neutra Blue Lilies (2011), one of a specific series of works begun around 2009-10, refers to the Austrian architect Richard Neutra, a major contributor to the shaping of the Los Angeles landscape as a mecca for a laid-back lifestyle in contact with nature, pioneering the use of new materials in residential architecture, something that Sarmento incorporates almost as an image in his painting. Many of the Los Angeles houses that captivated Sarmento with their morphology, their organic construction, the purity of their lines and their Minimalist aesthetic have become authentic icons, and some have had a significant cinematic presence as film sets, such as the Neutra house we see in Curtis Hanson’s 1997 L.A. Confidential, based on the neo-noir novel of the same name by James Ellroy.

Carlos Garaicoa also studied architecture, and makes good use of it in his reflections on the decrepitude that besets his native Cuba. In The Word Transformed (2009) he combines the architectural structure of billboards with the language of propaganda to create collages that restore the integrity of dilapidated buildings. The installation, which consists of eight light boxes and a large table covered with cutting mats of the kind used by graphic designers, is a kind of architectural construct in its own right.

Juan Navarro Baldeweg is the only one of these artists to have practised architecture as a profession, in parallel with his researches into form in the field of the visual arts. The painting of interior scenes has a venerable tradition, but his two diamond-shaped works– Silver Room with Figure (2006) and Red Room with Figure (2005) – approach their theme in a way that is closer to the architectural plan or axonometric than to the space of a real room, while the drawing of the figure, which serves as an indicator of scale, takes the form of a decorative element.

A similar if more conceptual approach informs the work of Fernanda Fragateiro. Her installation consists of three elements: Elevation (Quiet Side); Ordinariness and Light, after Alison and Peter Smithson (2018); and Blue Window (2018) are all related to the Smithson’s Robin Hood Gardens social housing project, whose architecture, once emblematic of the Modernist utopia, came to exemplify the shortcomings of that paradigm. Years of campaigning by architects and heritage organisations failed to prevent the demolition of one of the post-war Brutalist housing blocks in 2017, in what the artist regards as an act of institutional vandalism. At the time, she was working on Elevation (Quiet Side) (2018), an aluminium grid which mimics the west façade of the residential complex. With this work Fragateiro created, in real time, a fictional archaeology: in her sculpture the force of the Robin Hood Gardens utopia rises up against its demolition and against the savage neoliberal policies that time and again, have been directed at destroying modern collective housing and with it the promise of resolving the housing problems of ordinary people. The structure of the oversized mural relief replicates the gigantic façade of one of the buildings and points to how the over-rationalising of dwelling may fail to consider the specific needs of the actual resident. In this way, Fragateiro questions the purposefulness of the modernist utopia, in some sense equating it to conceptual sculpture.

This critical approach to architecture as a construct also feeds the work by Muntadas. Fences (2009) is a series of twelve photographs of the gated entrances to houses in residential areas of São Paulo which invites us to reflect on the way in which, when trying to keep their property safe from strangers, people end up walling themselves in, transforming their home into a kind of prison and thereby turning the whole concept of security inside out.

Julie Mehretu also reflects on the significance of the architectural space as a framework for social structures and interactions. The artist has made frequent references in her work to architecture, using technical drawings and the silhouettes of buildings as the basis for many of her compositions. Epigraph, Damascus (2016) is a polyptych of etchings that forms part of a body of work in which Mehretu engages with the destruction caused by the civil war in Syria.

‘For years, Mehretu has used architecture and its representation as the basis of her work, not in an obvious way, but as a background, something we can appreciate throughout the history of art when we think about many of the paintings that have a landscape in the background, such as the Mona Lisa.’ So writes Benjamin Weil, for whom this landscape creates the context that enables us to understand the foreground. In Mehretu’s case, architecture establishes the idea of order, of social organization delimited by the architectonic urban plan, expressed in a free visual language which derives from a very established structure: architecture.A catalogue will be published as a complement to the exhibition, with texts by each of the artists in which they discuss their relationship with architecture.